Introduction

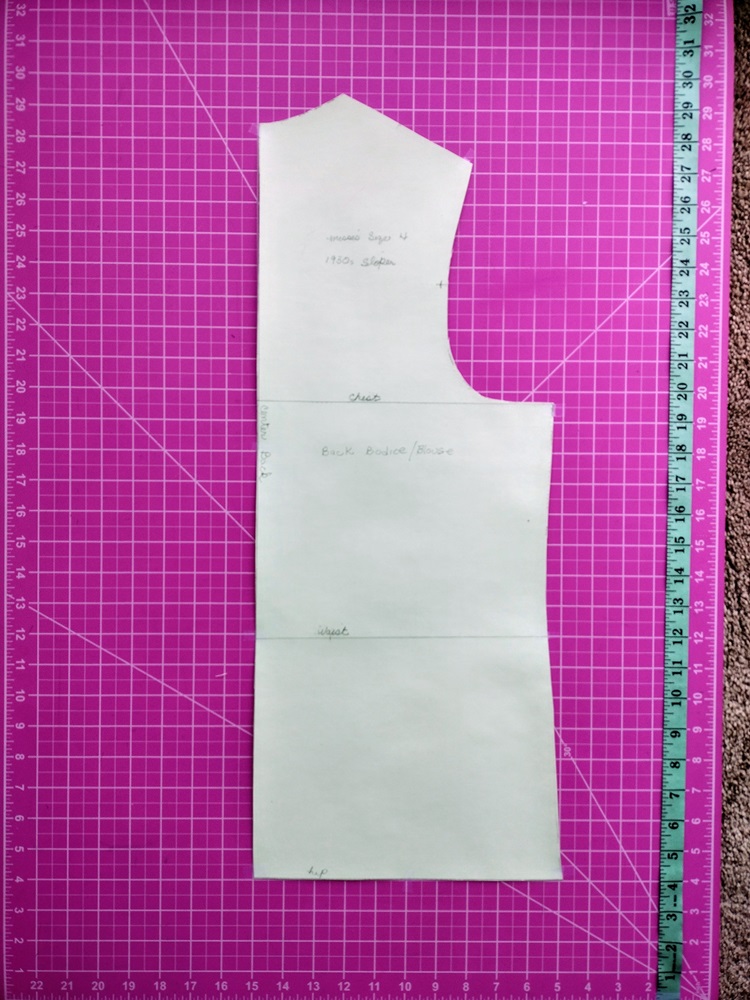

I am happy to share with you my hand drafted slopers that can be used to create styles with a 1930s feeling. The slopers are in a Standard Misses Size 4. The patterns were drafted with 3″ of style ease added to upper arm, chest, bust, and hips. The waist has 1 1/4″ ease added.

I did not use a period drafting system to save time. Instead I used the French Fashion Academy drafting technique which I learned in school. I think the results come close to capturing the pattern shapes in the 1930s drafting and sewing books I used for reference.

I release the slopers into the commons. The photos may be downloaded and used in a graphics program like Adobe to refine, grade, print and use as you please.

Research used: 1930s Pattern Cutting and Sewing Books

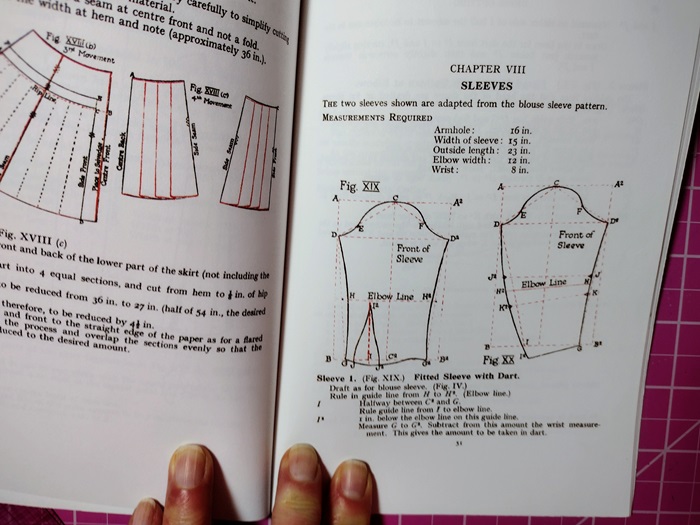

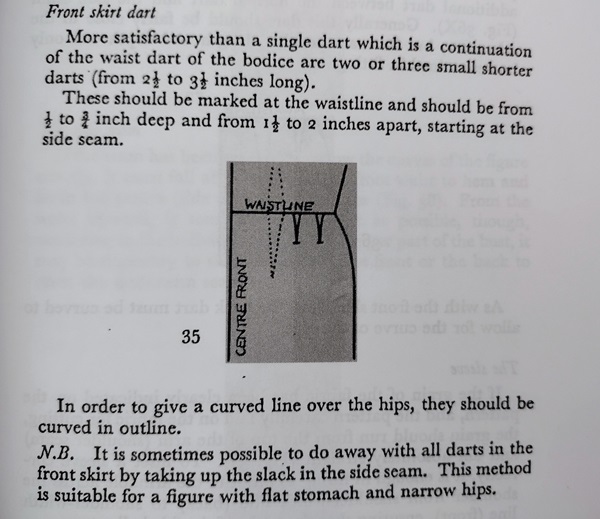

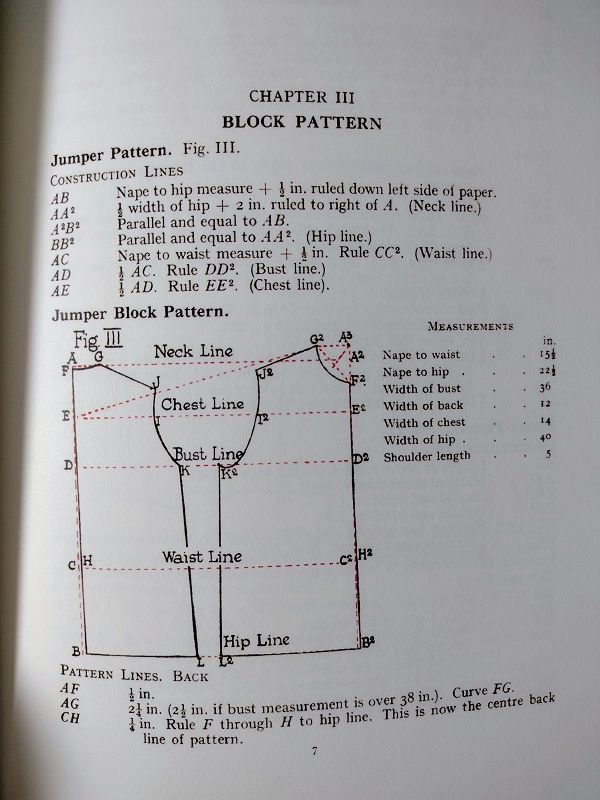

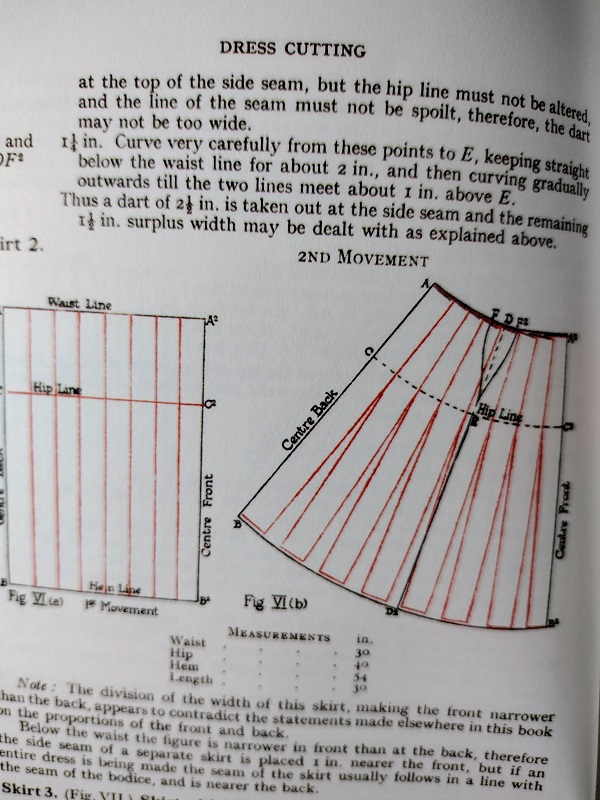

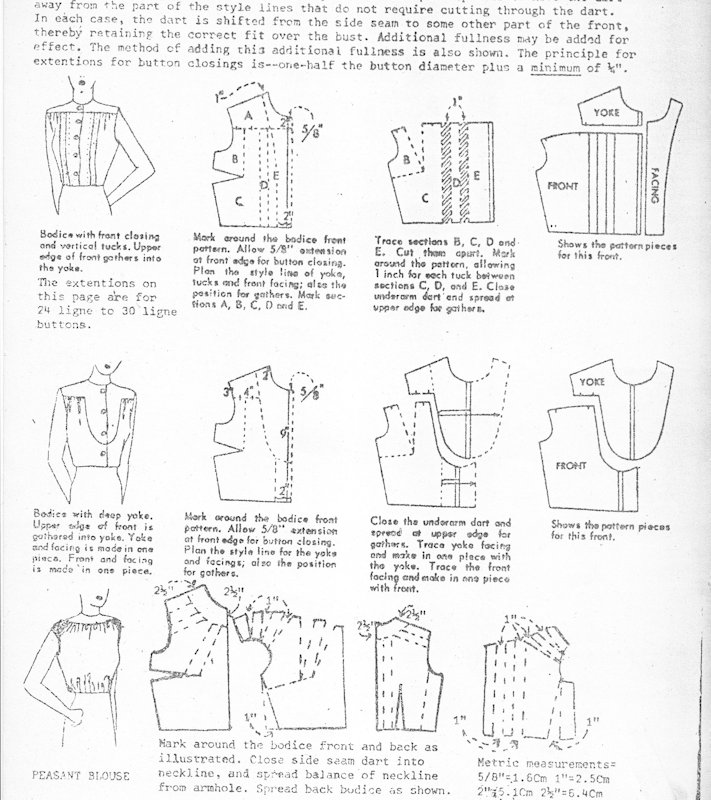

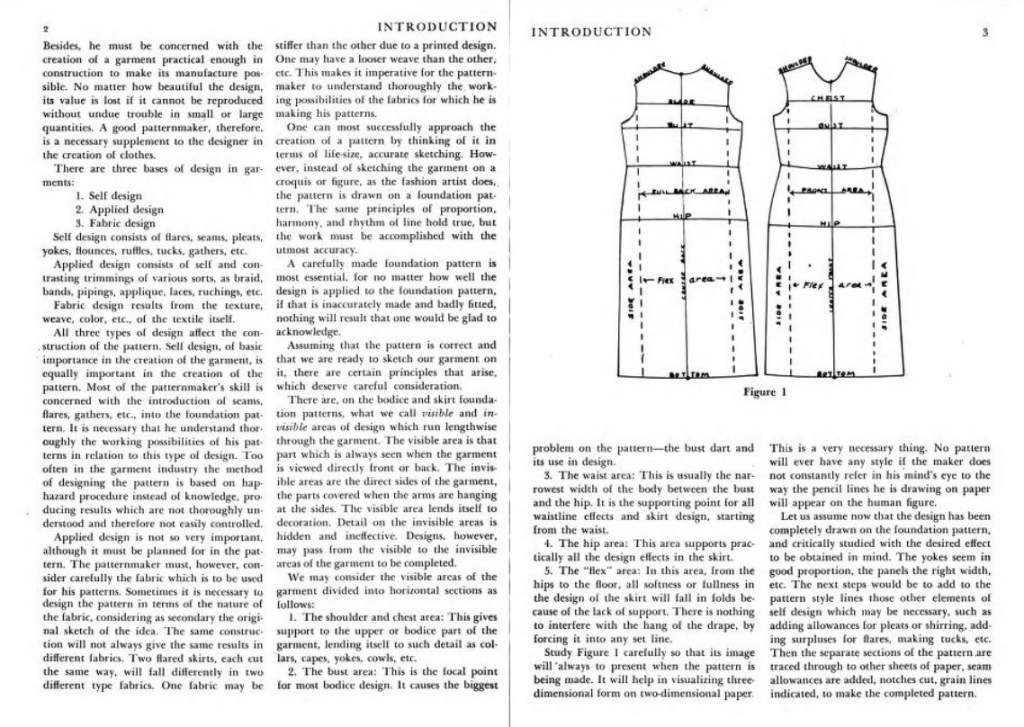

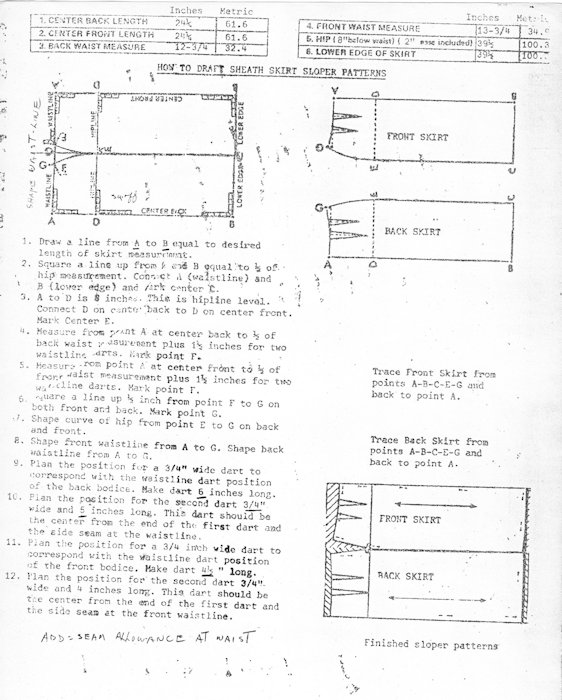

For the pattern shapes I used Dress Cutting by Margaret Ralston. Here are diagrams from the book for the bodice, sleeve and one of the basic skirts.

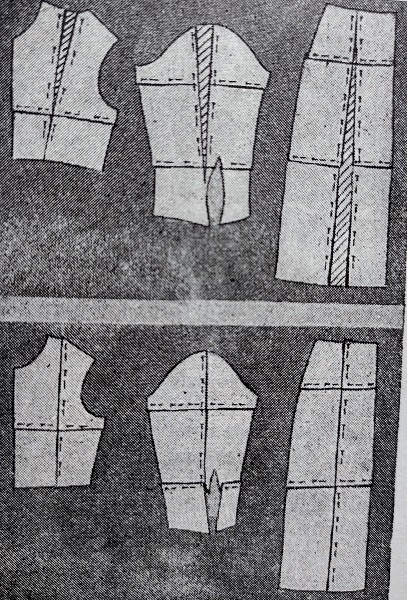

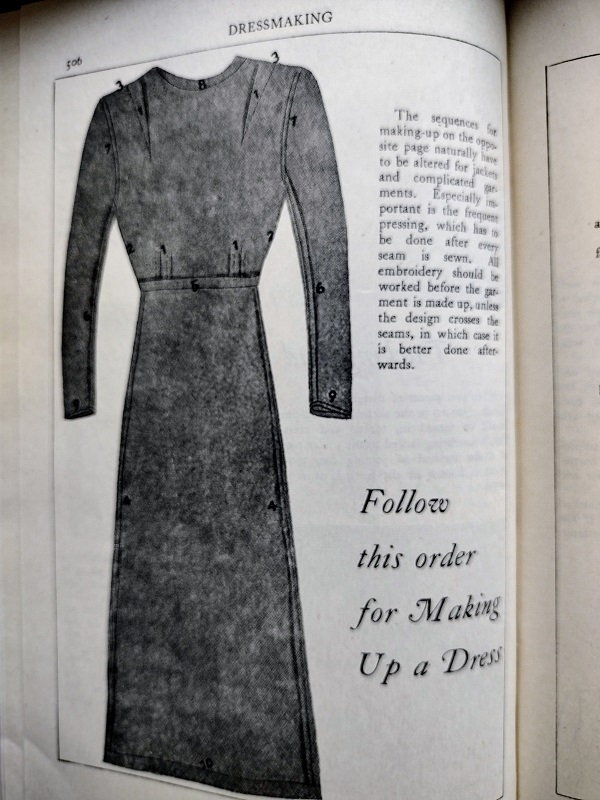

I referred to illustrations in Weldon’s Encyclopedia of Needlework as an additional step in learning about the shapes of basic patterns during the 1930s. Here are some illustrations from the chapter about fitting:

The results I obtained differ from the illustrations. The straight skirt is not as form fitting as a modern pencil skirt. The curve over the hip is softer and the skirt falls straight from the abodomen down. This is why I call it a “slim skirt”. I like the fit as it is not tight and it is not that form fitting in front or back.

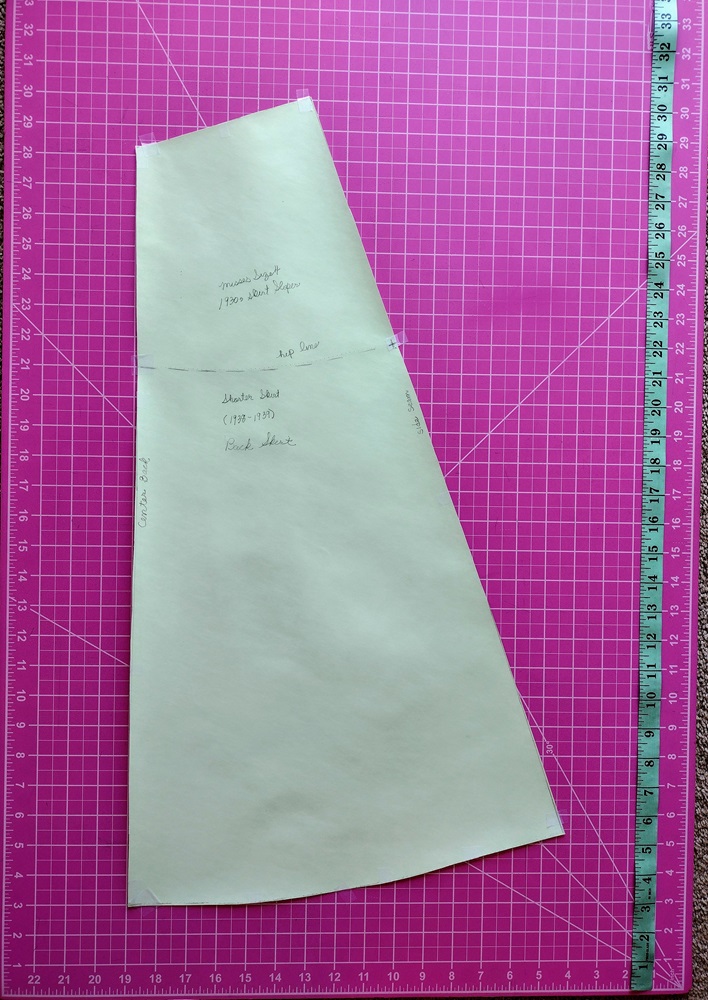

The slightly A-line and flared skirts do not fall as straight as the illustrations in Ralston’s book would have you think. I was surprised and pleased with the degree of flares each had. They are flattering and permit easy movement.

Hemline lengths differ during the 1930s

I bought scans of fashion illustrations from Etsy. These came from various sources and compiled by RetroKatDigital From the scans I saw that skirt lengths went to mid-calf length or lower from 1930 to about 1937. From 1938 to the end of 1939 hemlines went above mid-calf. The silhouette that became iconic during the 1940s was already evolving during 1938 and 1939. The shoulder line was more defined. The waistline was neatly nipped in and skirts had a more A-line shape that was less fluid, at least for everyday wear.

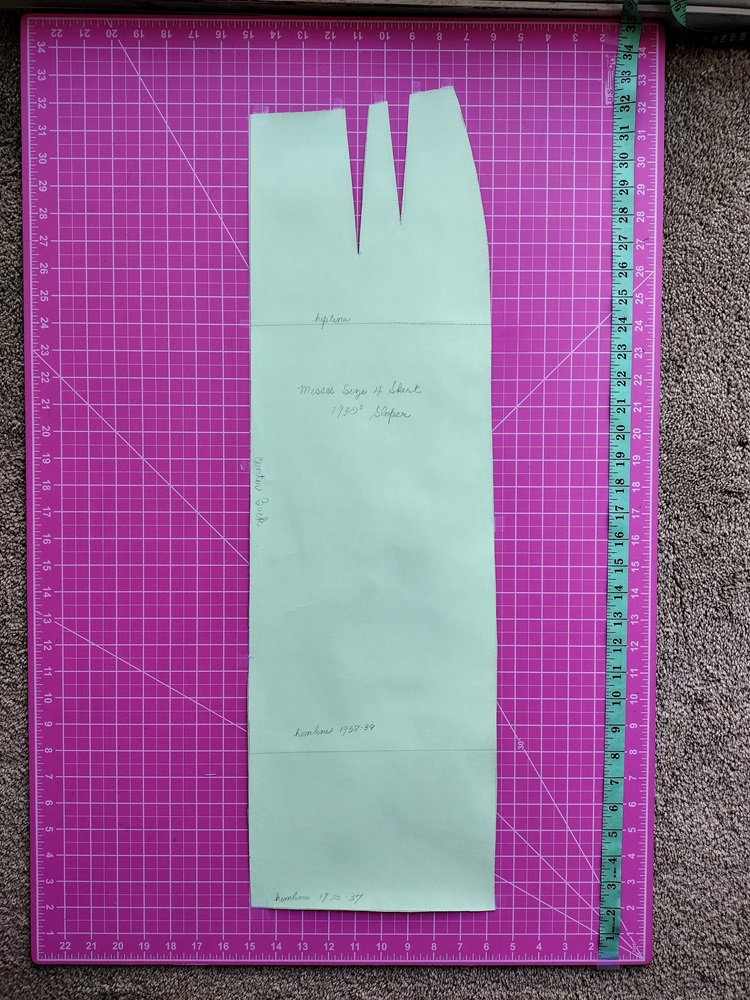

For this reason I marked two different hemlines on the slim skirt sloper. The shorter hemiline is for 1938-1939 inspired styles. The longer hemline is for styles influenced by fashions from 1930-1937.

I made a mid-calf flared skirt for 1930-1937 influenced styles. The sweep at the hemline is greater than that of the shorter flared skirt to be used for 1938-1939 influenced styles. The shorter skirt also has less flares.

The Bodice-Blouse Sloper and Fitted Vertical Dart Sleeve

The sloper for the bodice-blouse ends at the hipline (8″ below the waist). The waistline is also marked. This way the sloper can be used for a blouse or the bodice of a dress. I chose an unfitted sloper because this shape agrees with what Ralston shows in her book. When used for a dress, the extra style ease can be gathered into the waist. Another approach is to make a toile, and then drape in tucks or small darts.

The vertical dart in the sleeve can be transformed into gathers that fit into a cuff. The effect is a very modified Bishop Sleeve. The sleeve can also be transformed into a sleeve with a point at the wrist. It can be cut above the elbow to make short sleeves, flared sleeves, bell sleeves and other kinds of sleeves.

Special Notes

–The measurements used for the sloper are the Basic Misses Size 4 plus 3″ ease to chest, bust, hips, and upper arm. The waist has 1 1/4″ ease.

–Always make a muslin to customize the fit or check that it is in line with the size 4 you use.

–Seam allowances of 1/2″ to 5/8″ must be added when cutting.

–The French Fashion pattern making system moves side seams of tops, bottoms and slaeves 1/2″ to the back of where the side seam is on the form or where it would be in mass manufactured clothing. This is done to create a better fit.

–The toiles are fitted over a one piece slip. This enables me to determine if the final fit has enough ease. It also improves the look of how the garment will drape over the form.

The Sloper: Unfitted Bodice with Fitted Sleeve (vertical dart)

The Sloper: Slim Skirt

The Sloper: Flared Skirt, longer length

The Sloper: Flared Skirt, shorter length

You must be logged in to post a comment.