Introduction

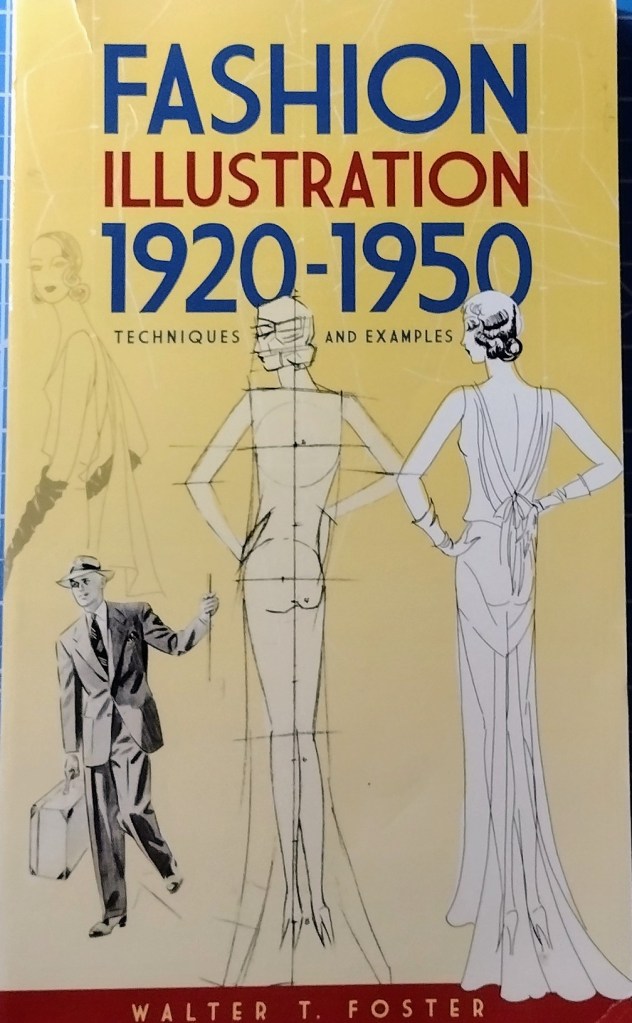

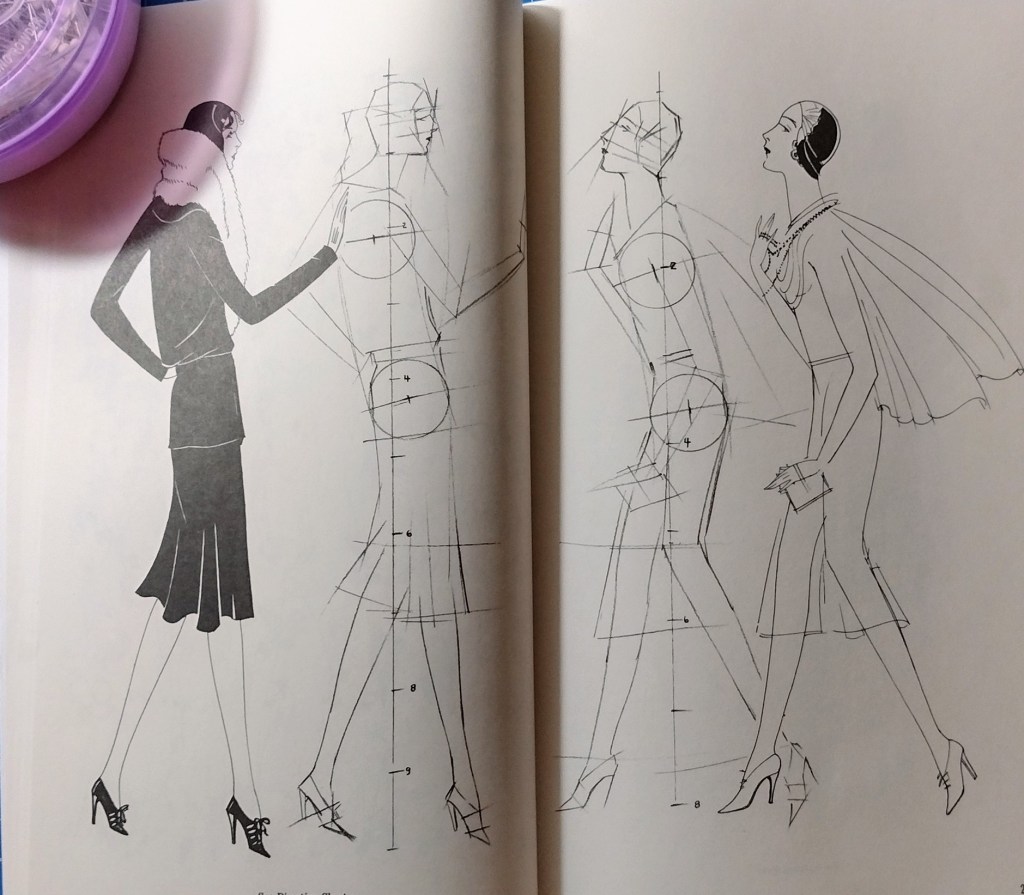

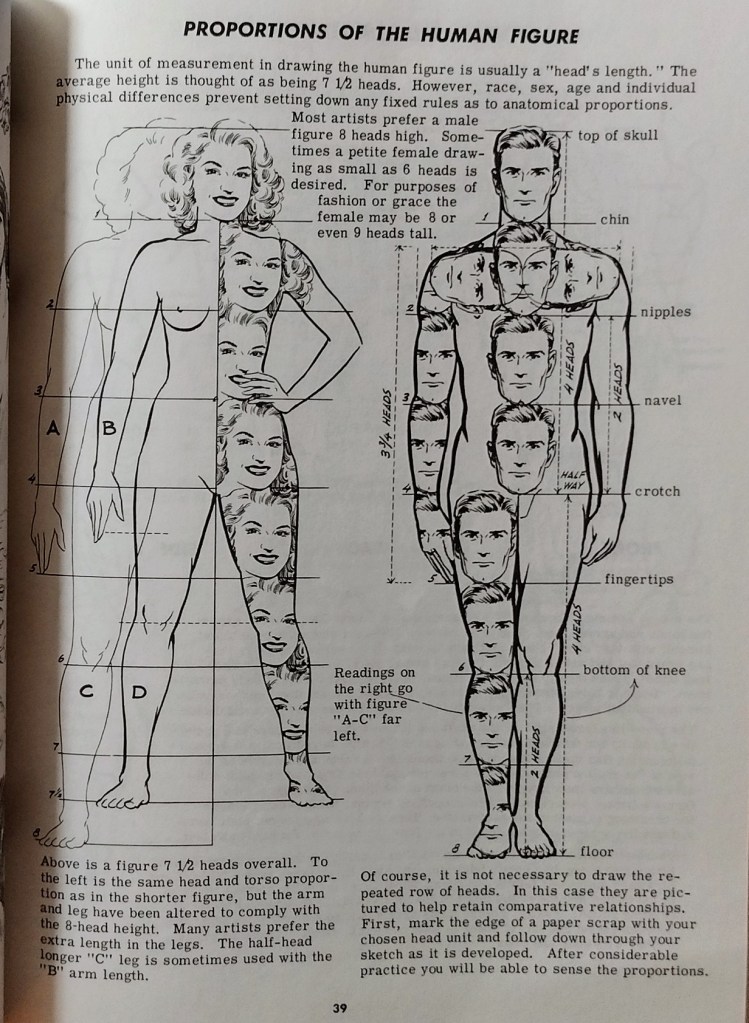

This week I reviewed the first sketch made for my next project, a 1930s inspired skirt and blouse. I do not have much experience working with styles of this decade, so it is a big challenge for me. I have only made one dress using design elements from a 1930s book, Paris Frocks at Home. That dress was designed as what I envisioned a woman would have as a special occasion dress during the Great Depression. It was pretty enough for a semi-formal occasion and yet could be worn for more everyday events such as a Sunday visit.

With my new project I am envisioning how a woman would dress for work during the 1930s. I want the skirt and blouse to be pretty and attractive enough to be wearable for today. For this reason I am taking only certain elements from the 1930s, not all of them.

I re-thought the first sketch and was not satisfied with it. I will detail the reasons here while sharing the importance of maintaining a clear focal point for any design.

What is a focal point?

A focal point is that part of the outfit where you want to:

–direct the gaze of the viewer

–emphasize a feature and make it attractive

–express an idea about the outfit, i.e. what is the message

Importance of integrating a focal point into the flow of the design

A focal point must be in harmony with the overall appearance and purpose of the outfit. It has to have pleasing proportions and add to the wearers attractiveness. Learning how to balance focal points takes experience. You want at least one, perhaps two. But never so many that the eye does not rest on any particular area and then move to what feature you are emphasizing. For example, in Version 1 of the 1930s outfit there are, I think, conflicting focal points. The scalloped yoke of the skirt competes with the bow of the blouse.

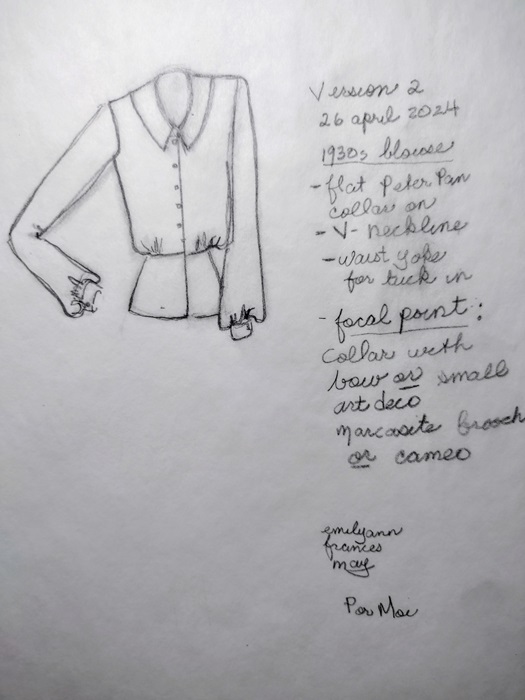

Version no. 2 of the skirt and blouse appears more calm and pleasing to the eye. The flounce at the bottom of the skirt emphasizes the movement when the wearer walks. A second focal point is the v-neckline of the Peter Pan flat collar. A small, marcasite Art Deco broach can be pinned at the neckline to create a second focal point. Or, very pretty but small buttons may be used to create the second focal point. Here there is a more sublte play between the focal points that Version no. 1 lacks.

How to compare focal points and choose the right combinations

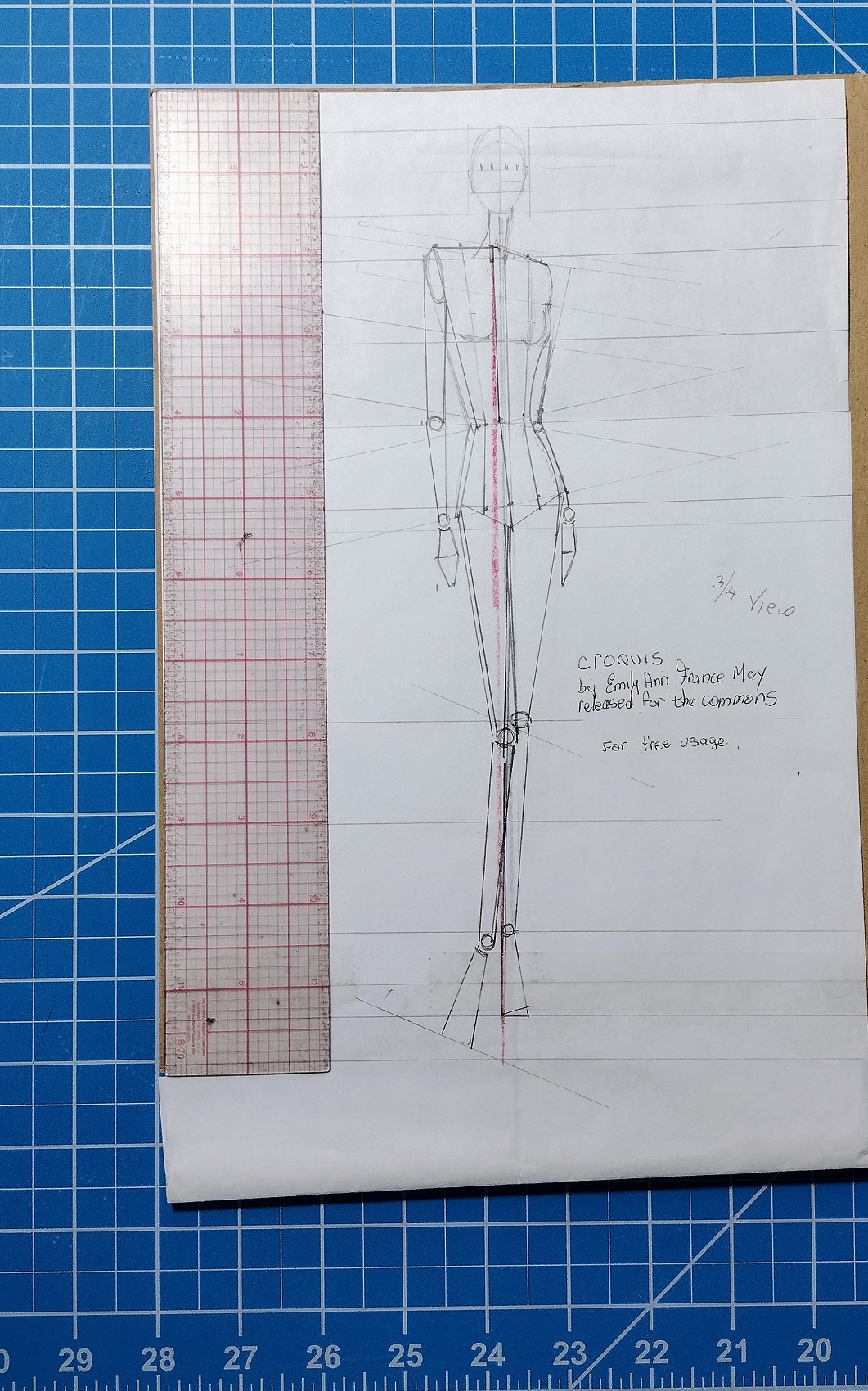

One way to choose the right combination of focal points, or choose to have just one focal point, is to make separate sketches of the parts of the outfit. Then make a complete sketch of the outfit put together.

1930s skirt and blouse sketches and notes, Version no. 1

1930s skirt and blouse sketches and notes, Version no. 2.

If doubts remain about the current pairing of separate parts of the outfit, the sketches of the garment pieces can be mixed and matched. This gives some idea on how the elements might or might not work together in a different combination.

Blouse Ver. no. 2 is paired with Skirt Ver. no. 1 on the left. On the right Blouse Ver. no 1 is paired with Skirt Ver. no. 2.

It helps if the sketches are put aside for a day or two. Then they can be reviewed again with a fresh point of view. When performing this review, be aware of what first captures your attention. Then consider how that first focal point works with other elements in the design.

Through this process of sketching, considering, studying and planning you will come up with an important and clear definition of how to proceed in the next steps of your design plans.

My final choice: Version no. 2

Additional Resources

To learn more about focal points in fashion please visit:

UEN Utah Education Network

Emphasis_the_Focal_Point_of_Fashion_1_.pdf

Scroll down and on the right side of the screen are free course materials you can download that will help you understand what the focal point is about.

Purfe: Fashion, design and perfect fit

“Basic Principles of an Outfit Layout: Focal Point”

October 14, 2012

by Olga

You must be logged in to post a comment.