I bought this book through Amazon under the title “Pattern Making: Drafting 1930s Lingerie, Blouses, Skirts & Sportswear Fashions” by Gertrude Mason. The book was originally titled “Gertrude Mason’s Pattern-Making Book” and published in the U.K. in the 1930s. Ms. Mason was, according to the title page in the reprint I purchased, “a lecturer demonstrator in needlework, dressmaking and tailoring under the Board of Education, The Birmingham Education Committee and the Kent Education Committee.”

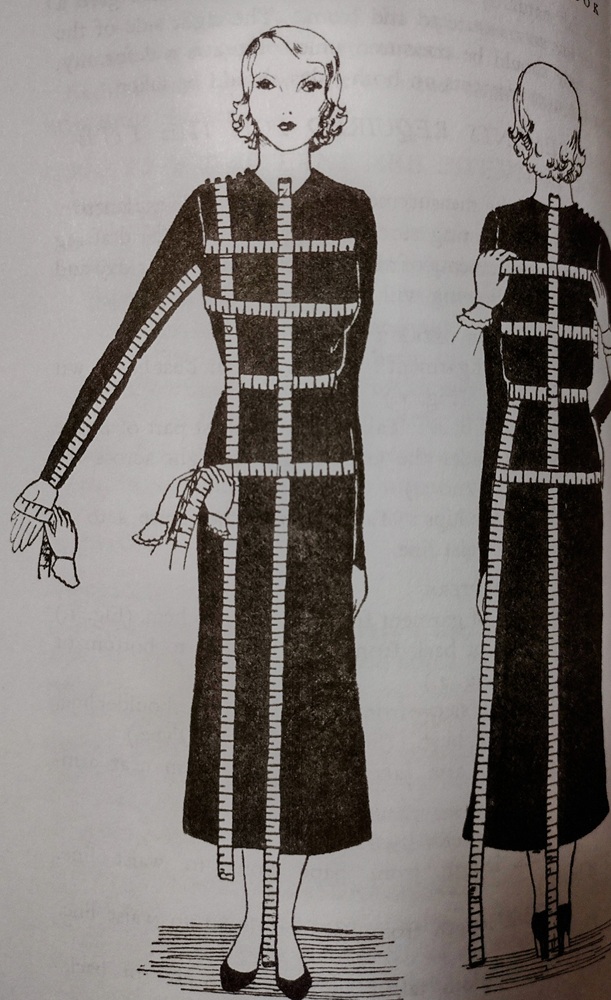

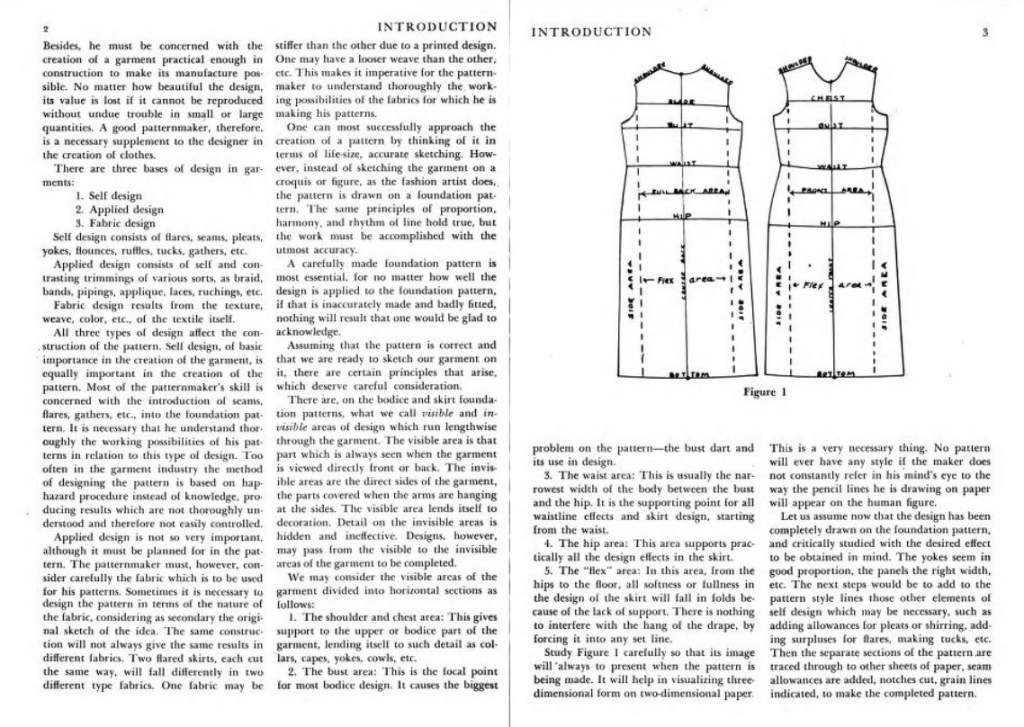

This book may have been part of demonstration materials or course materials for Ms. Mason’s work. In a demonstration or class, there would be hands-on exposure to fitting challenges or times when the resulting pattern did not conform to the examples given in the book. Explanations would be provided. That is why I think this book was intended for such use. It is not the kind of book that makes fitting and altering the results easy for the beginner. This book also lacks a personal touch that would guide the patternmaker along the way. There is little introduction or explanation at the start of each chapter. Instead the reader goes right into instructions for drafting each pattern. The approach is step by step, along with clear illustrations of the resulting pattern. However, at no time are any comments or notes given to explain what should be done if the resulting pattern does not turn out as illustrated.

My review is based on my personal experience using the drafting system and pattern transformations in this book. I followed the chapter on taking measurements using my Wolff professional dress form size 8. The basic patterns for what is called The Magyar and the simpler wraps turned out acceptable, but not outstanding. The results were very loose and could easily be made using a modern day sloper and transforming for a mounted (a/k/a grown-on) sleeve. These early patterns are all unfitted, boxy and without darts. Tucks, pinch pleats, and shirring could be added as shown in the illustrations, but no written instructions are provided.

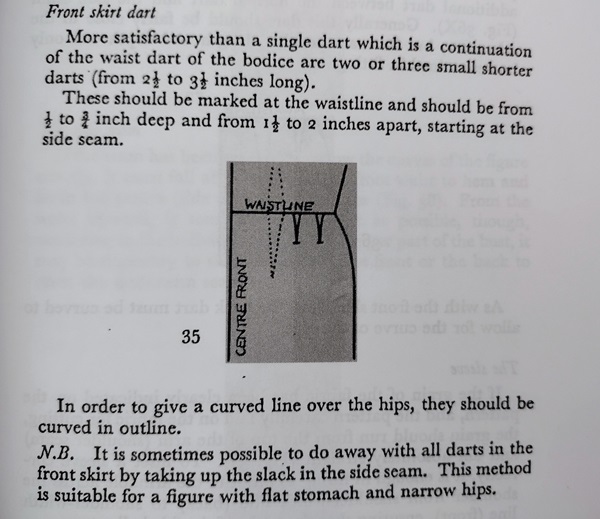

I then tried drafting the basic skirt pattern using the measurements from my Misses Size 8 dressform. Following the instructions I ended up with a very large back dart on the skirt. I divided the width into three separate darts. Still the skirt did not fit well across the front. The front ended up not being dartless but needing one dart on each side of center front. The resulting skirt was wide at the bottom but did not have the flow and movement of a modern A-line or flared skirt.

There must be adjustments that could be made but overall I did not find the effort worthwhile. I used up a lot of pattern paper and muslin to test the results of this patternmaking system. I could have adapted my modern slopers. Each chapter has a set of measurements used as an example for drafting each pattern. The calculations for each step are also provided. The basic body measurements used in the book are close to a Standard U.S. Misses Size 8. I may revisit this book and use those measurements to draft the patterns. I could then alter the toile to fit my modern Wolff size 8 dress form. From that I could make a sloper. That is one route others can take if they are interested in standard sizes and slopers.

This book does have value for the historical information it provides. Also the illustrations of the transformations can serve as a guide to drafting or adapting any modern patternmaking system to get similar results. In the end, I think it is more important to achieve perfect fit with a vintage look than having to use a vintage pattern drafting system that results in poorly fitting clothes or results that can be easily reproduced with a modern drafting system with perfect fitting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.