Introduction

Emily Wilkens was an American designer who came to prominence during the 1940s. What Emily designed at that time was considered new, innovative and an important development in the fashion industry. Until the late 1930s-early 1940s, clothing for pre-teens mirrored the clothing for little girls. Teenage girls between the ages of 13-19 had choices, although not attractive ones for their developing figures and personalities. Some designers created clothing sized for the teenage body but that looked very much like that of a little girl’s outfit. Other designers worked with inspiration from the clothing for mature women and sized them for teenage girls. The result was that there was little that was fresh and new until Emily Wilkens set her focus on the developing teenage market.

Emily Wilkins’ Contributions to Fashion

Original sketch and dress with smocking for teenage girls, designed by Emily Wilkens.

“Young Originals” is as much the story of Emily Wilkens as a designer as it is about the birth of her design label Young Originals.

Researcher and writer Rebecca Jumper Matheson has created a book that is informative and exciting to read. She presents an excellent view of the market forces that brought the teenage girl into focus and made her the center of Emily’s design vision. Teenagers were coming into their own by the 1940s and were emerging as a separate market with unique needs and desires. Emily was part of this trend that marked a definite break with the past.

Tee Matheson was one of Emily’s favorite teenage models during the 1940s.

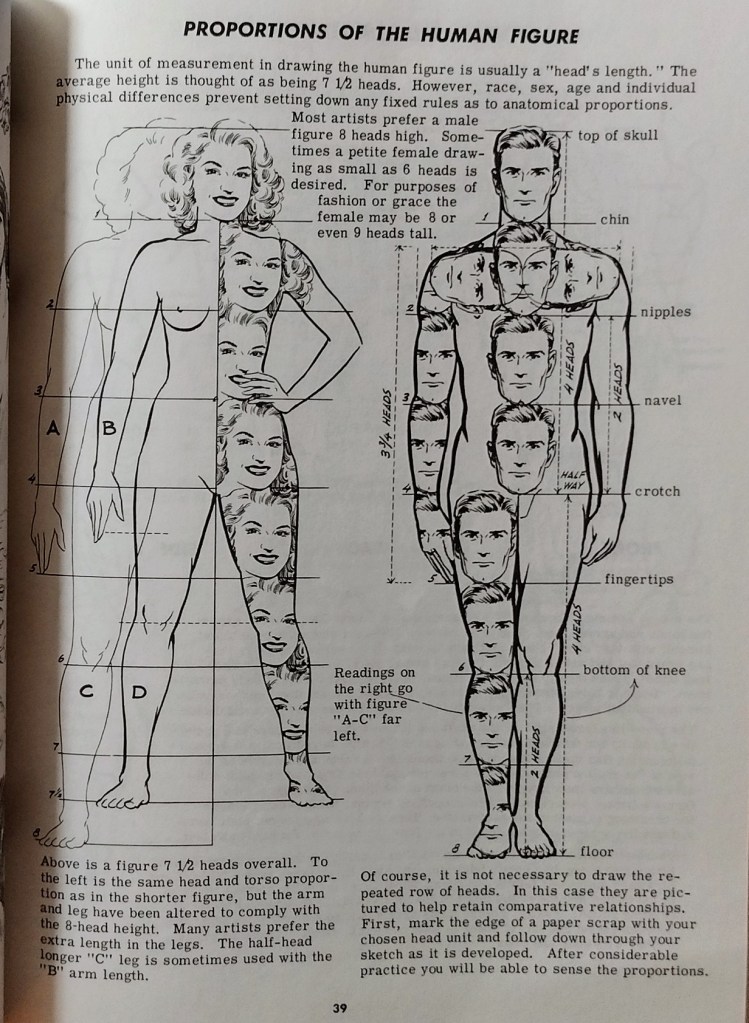

Emily’s ideal model was healthy and radiated a confident beauty. She did not need much make-up, jewelry or fancy hairstyling. Well fitting clothing, tasteful accessories and attention to healthy hair, skin and body were what mattered. Emily sought to free the teenage girl and young woman from the artifice put before the public as a standard of beauty. The famous actress of Hollywood was not an image for Emily. Instead she wanted teenage girls to look at themselves in the mirror and work with what would be most flattering to them.

Evening gown for a teenage girl or young woman, by Emily Wilkens.

Although she set a new trend, Emily’s fashions were very modest when we look at them today. In fact from our vantage in time they do not seem as they did when they made their debut. If anything some of Emily’s dresses look a bit too little girl and not enough for the young woman developing during the teen years. Still there is a fresh, easy going quality to her designs that can be adapted to the styles of the past that inspire modern sewistas, patternmakers and hobbyists.

Sketch of one of Emily’s designs.

The book contains many technical sketches of Emily’s designs, as well as photos from private collections. From a photo of an Emily Wilkens label in this book, I got an idea of how I wanted the labels made for my own dressmaking creations. I also like the details on some of her dresses like the bows and appliques. Her use of gloves and handbags also inspires me when I need to draw on how accessories made her total look for teenage girls unique.

Label used for Emily Wilken’s designs.

I recommend this book to dressmakers and hobbyists with an interest in fashion history. You will learn how the market for teenage clothing for girls and young women started. This knowledge will enrich your understanding of how fashions for this market segment continued rapid growth during the 1950s, 60s and beyond.

You must be logged in to post a comment.